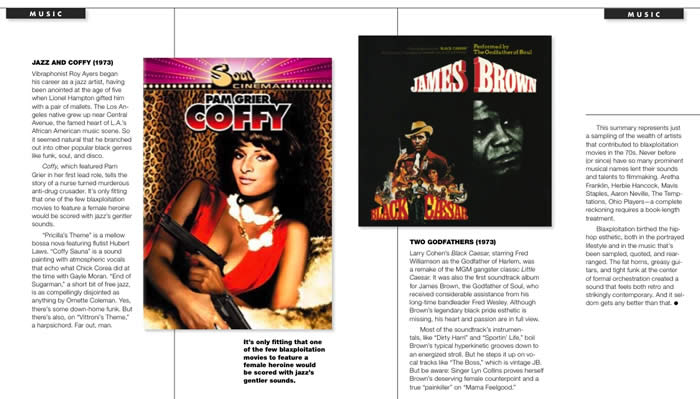

TWO GODFATHERS (1973)

Larry Cohen’s Black Caesar, starring Fred Williamson as the Godfather of Harlem, was a remake of the MGM gangster classic, Little Caesar. It was also the first soundtrack album for James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, with considerable assistance from his long-time bandleader Fred Wesley. Although Brown’s legendary black pride esthetic is missing from this album, his heart and passion are in full view.

Most of the instrumentals, like “Dirty Harri” and “Sportin’ Life”, soften Brown’s usually hyperkinetic grooves down to an energized stroll. But he steps it up on the vocal tracks like “The Boss”, probably the best known cut and vintage JB. Singer Lyn Collins on “Mama Feelgood” proves herself to be Brown’s female counterpoint and a true “painkiller”.

JAZZ AND COFFY (1973)

Vibraphonist Roy Ayers began his career as a jazz artist, having been anointed at the age of 5 when Lionel Hampton gifted him with a pair of mallets. The Los Angeles native grew up near Central Avenue, the famed heart of LA’s African American music scene, so it was natural that he would branch out into other popular black genres like funk, soul and even disco.

Coffy, Pam Grier’s first lead role, tells the story of a nurse turned murderous anti-drug crusader, and it’s fitting that one of the few blaxploitation movies with a female heroine would be scored with the gentler sounds of jazz.

“Pricilla’s Theme” is a mellow bossa nova featuring flutist Hubert Laws. “Coffy Sauna” is a sound painting with atmospheric vocals similar to what Chick Corea was doing with Gayle Moran at the same time. “End of Sugarman”, a short bit of free jazz, is as compellingly disjointed as anything by Ornette Coleman. Yes, there’s some down-home funk but there’s also, on “Vittroni’s Theme”, a harpsichord.

This is only a sampling of the wealth of artists who contributed to blaxploitation movies in the ‘70’s. Never before nor since have so many huge musical names lent their sounds and talents to filmmaking. Aretha Franklin, Herbie Hancock, Mavis Staple, Aaron Neville, The Temptations, Ohio Players; a complete reckoning would require a book-length treatment.

Blaxploitation birthed the hip hop esthetic, both in the portrayed lifestyle and in the music that’s been sampled, quoted and re-arranged. The fat horns, greasy guitars and tight funk at the center of formal orchestration create a sound that feels both period and strikingly contemporary.

Kingpins, junkies, private dicks and vigilantes. Handsome, athletic men sporting wide-lapelled pimp suits or leather jackets accompanied by gorgeous women in miniskirts and palazzo pants. Borsalino fedoras perched on puffy ‘fros and everyone teetered cautiously on ridiculously high platform shoes. No, there's nothing like looking back at the ‘70’s era known as Blaxploitation. And while we might giggle at the fashions, the comically bad kung fu (Dolomite!) and the sometimes-sketchy production values (unintelligible dialogue, blood squibs that explode before someone gets shot), the music has stood the test of time.

Just as the hippie movement of the late ‘60’s transformed rock music that, in turn, became a touchstone and unifying force, a parallel cultural shift was taking place in black America. The civil rights and Black Power movements fueled the black pride ethos, seeping into the work of black artists whose music circled back to reinvigorate the faithful. The composers and musicians who scored blaxploitation films sat in the red-hot center of the zeitgeist, combining the new funk grooves that evolved from R&B with socially conscious, in-your-face lyrics.

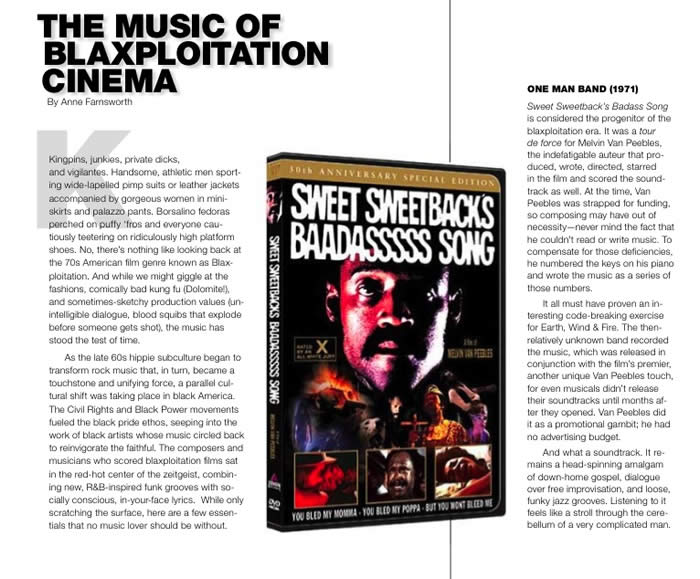

ONE MAN BAND (1971)

Sweet Sweetback’s Badass Song is considered the progenitor of the blaxploitation era. It was a tour de force for Melvin Van Peebles who produced, wrote, directed and starred, while scoring the soundtrack as well. The indefatigable auteur was strapped for funding so composing the music may have been an act of necessity, never mind the fact that Van Peebles couldn’t read or write music. He numbered the keys on his piano and wrote the music as a series of those numbers.

That must have been an interesting exercise in codebreaking for Earth, Wind & Fire, the then relatively unknown band who recorded the music. It was released with the film’s opening, a Van Peebles innovation, for even musicals didn’t release their soundtracks until months after they opened. Melvin did it for the promotion; he had no advertising budget.

The soundtrack is a head-spinning amalgam of down-home gospel, dialogue over free improvisation and loose grooves in the funky jazz vein. Listening to the soundtrack feels like a stroll through the cerebellum of a very complicated man.

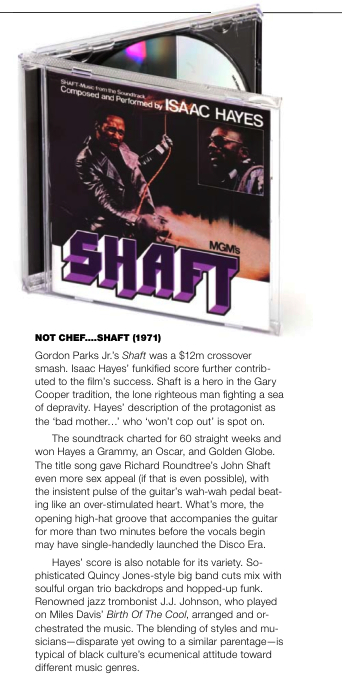

NOT CHEF… SHAFT (1971)

Gordon Parks Jr.’s Shaft was a $12m crossover smash and Isaac Hayes’ funkified score certainly contributed to its success. Shaft is a hero in the Gary Cooper mode, the lone righteous man fighting a sea of depravity and Hayes description of him as the ‘bad mother…’ ‘who won’t cop out’ was spot on.

The soundtrack charted for 60 straight weeks and won Hayes a Grammy, an Oscar and a Golden Globe. The title song gave Richard Roundtree’s John Shaft even more sex appeal, as if that were possible, with the insistent pulse of the guitar’s wah-wah pedal beating like an over-stimulated heart. For better or worse, the opening high-hat groove that accompanies the guitar for over 2 minutes before the vocals begin may have single-handedly created the disco era.

Hayes’ score is also notable in its variety. Sophisticated Quincy Jones-style big band cuts mix with tracks of soulful organ trio and hopped-up funk. The renowned jazz trombonist J.J. Johnson, who played on Miles Davis’ Birth Of The Cool, arranged and orchestrated the music. This blending of styles and musicians, disparate yet claim to the same parentage, is typical of black culture’s more ecumenical attitude toward different music genres.

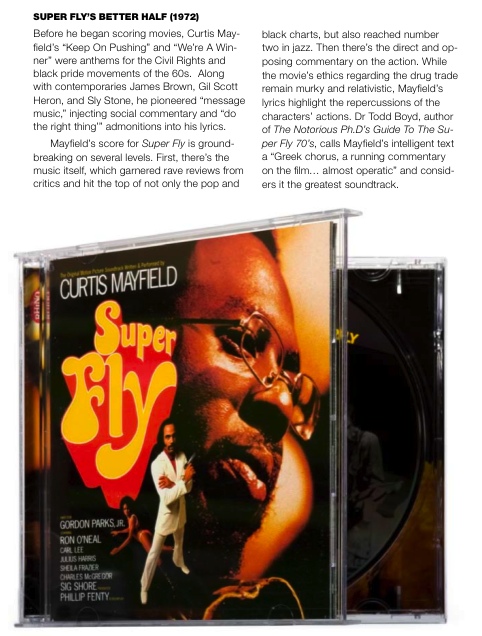

SUPER FLY’S BETTER HALF (1972)

Before he began scoring movies, Curtis Mayfield’s “Keep On Pushing” and “We’re A Winner” were anthems for the civil rights and black pride movements of the ‘60’s. Along with his contemporaries James Brown, Gil Scott Heron and Sly Stone, he pioneered ‘message music’, injecting social commentary and ‘do the right thing’ admonitions into his lyrics.

Mayfield’s score for Super Fly is groundbreaking on several levels. First, there’s the music itself, which garnered raves from critics and hit the top of not only the pop and black charts, but also reached number two in jazz. Then there’s the direct and opposing commentary on the action. While the movie’s ethics toward the drug trade are murky and relativistic, Mayfield’s lyrics point out the repercussions of the characters’ actions. Dr Todd Boyd, author of The Notorious Ph.D's Guide To The Super Fly 70’s, calls Mayfield’s text a “Greek chorus, a running commentary on the film… almost operatic” and considers it the greatest soundtrack album ever made.

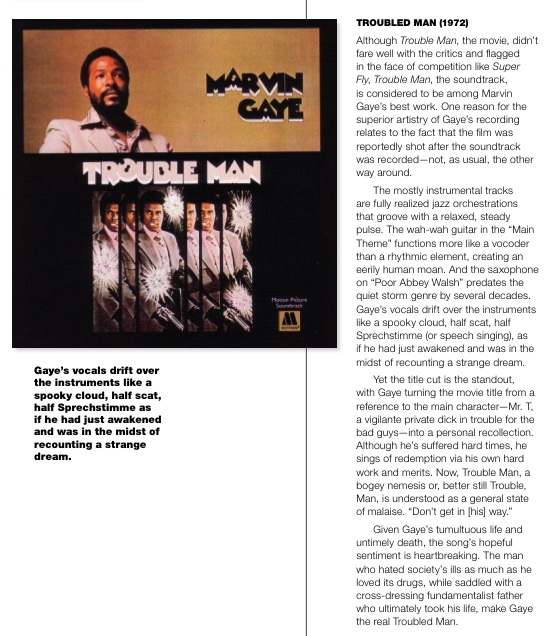

TROUBLED MAN (1972)

Although Trouble Man, the movie, didn’t fare well with the critics and flagged in the face of competition like Super Fly, Trouble Man, the soundtrack, is considered to be some of the great Marvin Gaye’s best work. One reason for the superior artistry of Gaye’s recording may be that the movie was reportedly shot after the soundtrack was recorded, not, as usual, the other way around.

The mostly instrumental tracks are fully realized jazz orchestrations that groove with a relaxed, steady pulse. The wah-wah guitar in the “Main Theme” functions more like a vocoder than a rhythmic element, creating an eerily human moan. The saxophone on “Poor Abbey Walsh” predates the quiet storm genre by several decades. Gaye’s vocals drift over the instruments like a spooky cloud, half scat, half Sprechstimme, or speech singing, as if he had just awakened and was recounting a strange dream.

The title cut is the standout, where Gaye turns the movie title from a reference to the main character, Mr. T, a vigilante private dick who’s trouble for the bad guys, into a very personal recollection. Although he’s suffered hard times coming up, he sings of redemption by his own hard work and merits, so that now Trouble Man, a sort of bogey nemesis or, with the addition of a missing comma, Trouble, Man, a general state of malaise, “don’t get in [his] way”.

In hindsight, considering Gaye’s tumultuous life and untimely death, the hopeful sentiment expressed in the song is heartbreaking. The man who hated society’s ills as much as he loved its drugs, saddled with a cross-dressing fundamentalist father who ultimately took his life, made Gaye the real Trouble Man.